Breaking the Codenames' code, or a fun Semi-Turing test

in Blog

Codenames is a competitive two-team game, whose objective is given one-word clues, a team that can link to multiple words on the board without mistaking those forbidden or belong to the other team, and performs best, wins. Despite the simplicity, it goes beyond the surface. Words are interlinked semantically, but day by day, existing link fortified and a new one created exponentially, thanks to pop culture, the evolution of language, or even shared experience amongst players. Therefore, many people find the game very exciting.

On one such occasion, I wonder if there is a sure-win strategy for the game. Instantly, I can think of an encoding scheme that embedding the keywords in one single move. However, code rarely conveys semantic link that people expect, and the fun lies in those meaning revealing moment. So more than often, you end up raising an eyebrow. A more legitimate way is that any words thrown out must establish a humanly acceptable link with the keywords. I find this challenge a weaker variant of Turing test: one human observes the game between two teams, knowingly one robot. He must tell from the picked clue, that it is machine-generated or comes from a natural mind. Without further ado, let me share with you my discovery.

Turing proposed that a human evaluator would judge natural language conversations between a human and a machine designed to generate human-like responses. The evaluator would be aware that one of the two partners in conversation is a machine, and all participants would be separated from one another.

\(\hspace{120pt}\) - Wikipedia -

You must learn to walk before you can run

To get warm-up, let’s start with the most simplified version of the game. As long as you follow the rule, no matter how nonsensical the clue is, your move is valid. In the game, there are 400 keywords in total. The board is a 5x5 grid of 25 squares, 9 are team blue’s words (blue agents), 8 are team red’s words (red agents), 7 are grey (innocent bystanders), and one is instant blackly lose (assassin). The blue team always plays first and must identify all blue agents before the red team finds their ones. The clue is a single word and a number, indicating how many keywords are associating with it.

As a sure-win move, blue team must come up with a clue that connects to their 9 agents and manage not to pick a red agent (their turn ends) or an assassin. At this point, some of you may have derived a solution. Hint: the words’ position is the key. You can stop now and think. I would get my milk coffee and be back soon, no peeking, okay?

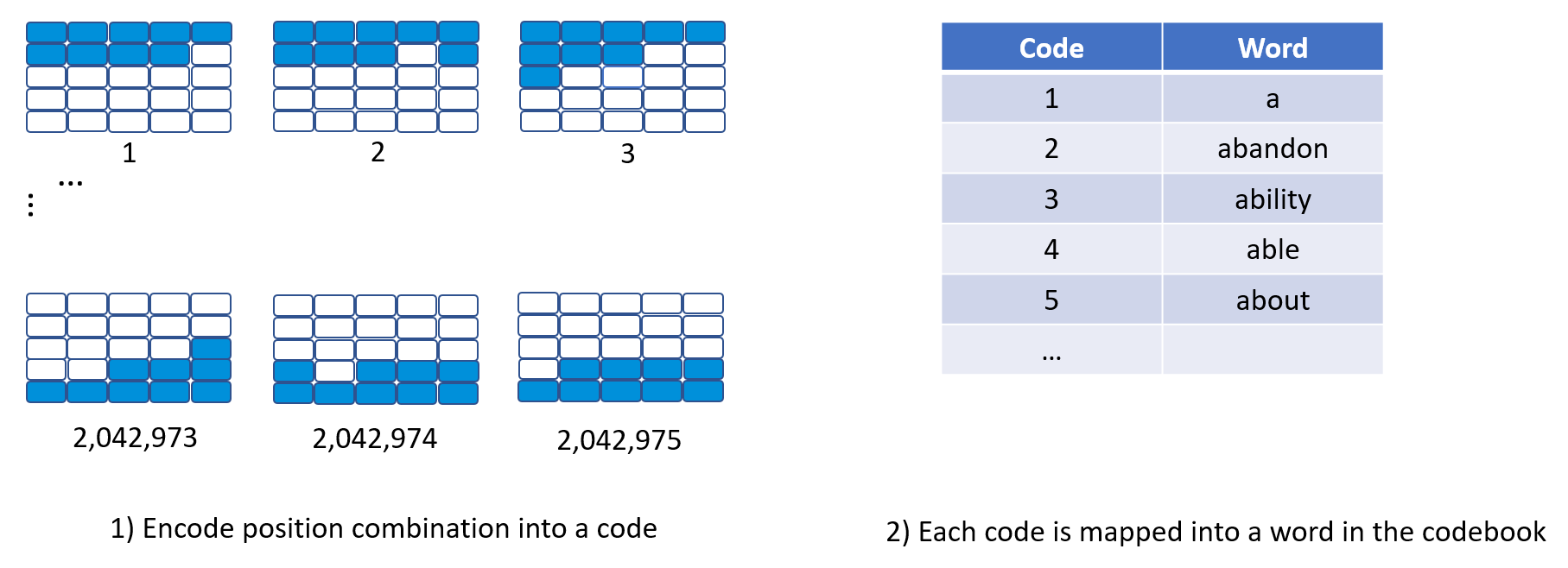

So here comes my tactic. You need two materials, 1) encode the positions of blue agents into …, a code; and 2) a codebook to map the code to an English word. To attain 1), we question ourselves: “How many possible combinations of 9 squares in a 25-square boardgame?” Easy peasy, \(C(n=25, r=9) = {25 \choose 9} = 2,042,975\). So a combination can first be mapped to a digit, out of 2,042,975 possible values. To have 2), look for the dusted family dictionary, their alphabetical order is the code. Voila!

It would be a perfect solution, except for a tiny detail. BBC says there are only an estimated 171,146 words currently in use in the English language. Luckily, the game has quite a limited number of map cards, hence far fewer combinations to consider. I believe they want all the cards to scatter evenly across the board; otherwise, one can say “top” and an easy grab of 5 words, which gives an unfair advantage to the other team.

I don’t have all the map cards at hand, but I bet if we scan through them all, more insight extracted, we can find a more efficient encoding scheme. Instead of combination, we can use word order or the gap between two adjacent cards as code materials. I hope that one of you can come up with a new one, and happily sharing with me.

Proposed encoding scheme with a 2,042,975-row codebook.

Proposed encoding scheme with a 2,042,975-row codebook.

A fancy ML codebook

You would no doubt no longer be invited to the next game night if using the above cheat. The clue does not convey any semantic link to pointed words is what it lacks. Gladly, data scientists do have a helpful toolkit for this occasion. Soonly replace Bag-of-Words when it first introduced, word vector method becomes a common practice to preprocess word token when fed into an NLP-related model, the neural network in particular.

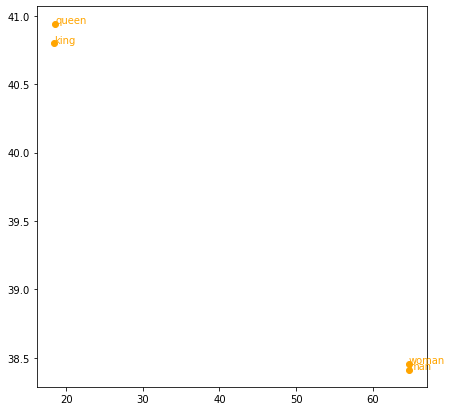

Learning vector space representation of words is often framed as a standalone unsupervised task, whose input a large corpus, i.e. text dataset, and output a collection of fix-length vectors, each corresponding to a word. As a result, the scalar distance (a function maps distance/angle between two vectors to a single numerical value) of a pair of word vectors, is proportional to how we think it’s semantically close. A typical example is dimensions of meaning: the expression “king is to queen as man is to woman” is indeed captured in the vector equation \(vector_{king} - vector_{queen} \approx vector_{man} - vector_{woman}\).

Vector equation \(vector_{king} - vector_{queen} \approx vector_{man} - vector_{woman}\) looks right. We project GloVe word vectors to 2D-space thanks to t-SNE, a visualization method retains the local and global difference between high dimensional data points.

Vector equation \(vector_{king} - vector_{queen} \approx vector_{man} - vector_{woman}\) looks right. We project GloVe word vectors to 2D-space thanks to t-SNE, a visualization method retains the local and global difference between high dimensional data points.

The key idea to encode word into such an arithmetic manner lies on two pieces of information: the co-occurrence of word pairs and neighbour words in a local context window. The former leverages the statistical characteristic, while the latter observes that words come together usually convey the same message or similar components of a bigger whole. Our word vector model of choice, GloVe, sides with the first approach and its objective - cost function - is defined as follows: \[J = \sum_{i, j=1}^V f(X_{ij}) (w_i^T\tilde{w}_j + b_i + \tilde{b}_j - \log{X_{ij}})^2 = \sum_{i, j=1}^V Term_1(X_{ij}) Term_2(w_i, \tilde{w}_j, b_i, \tilde{b}_j, \log{X_{ij}})\]

We denote \(X\) the matrix of word-word co-occurence counts, an entry \(X_{ij}\) denotes the occurences of word \(j\) in the context of word \(i\). \(w_i\) is the word vector of word \(i\), the dot product \(w_i^T\tilde{w}_j\) is a trick to map the vector difference into a single numerical value, bias \(\tilde{b}_j\) is another trick to ensure \(Term_2\) produces the same result when word \(w_i\) and \(w_j\) switch place. Intuitively, we train the word vector such that semantic distance of a word pair forced close to its (log) occurence, with a nice touch that the more popular a pair \((i, j)\), the less weightage on their (\(Term_1\)), hence gives more room for less frequent pairs to be recognized.

Enough of math, here is my idea to break Codenames: each word now can be represented as a data point, a high-dimensional vector. Consider all blue agents form into a cluster; we will compute a centroid (an average vector), then look for word closest to it. This is the clue, under the constraint that no agent from the other team or assassin nearby.

As a proof of concept, I have prepared a list of 25 words, and the cluster I would like to test is animal and country.

keyword_list = ['dragon', 'green', 'newyork', 'australia', 'pie',

'seal', 'wake', 'robin', 'pool', 'france',

'trip', 'duck', 'ham', 'shark', 'grace',

'spell', 'buck', 'dice', 'bow', 'spring',

'tube', 'ghost', 'brush', 'drill', 'cotton']

clustered_word = ['seal', 'duck', 'shark']

centroid = compute_centroid(glove_word_vector_dict, clustered_word)

print (centroid)

distance, word = find_closest_word_to_centroid(glove_word_vector_dict, centroid, clustered_word)

print ('Word represents for centroid:', word, distance)

print ('Words closest to centroid in decreasing in similarity order.')

distance_dict, sorted_words = find_closest_words_to_vector(glove_word_vector_dict, centroid, keyword_list)

for word in sorted_words:

print (word, distance_dict[word])

Output:

[ 0.35965732 -0.391844 -0.85795337 0.09057667 0.38060966 0.4850067

-0.58749336 -0.15278 0.7602666 -0.49245334 -0.07784335 0.7132533

0.90117663 0.96625996 0.02350167 0.06795999 0.40553665 -0.235831

-1.23233 0.27397 -0.275833 -0.5657067 0.595513 -0.3247843

0.09858334 -1.0315567 -0.13521235 0.6582633 0.17619233 -0.86915

1.3573667 -0.20295 -0.13896 0.77146 -0.29841268 0.44444

0.258672 -0.1362059 0.04270234 -0.72279334 -0.27866668 -0.01172899

-0.02446666 0.28056666 0.6844953 0.06487999 0.177436 -0.34573865

0.47711134 -0.11781999]

Word represents for centroid: cat 2.7491037845611572

Words closest to centroid in decreasing in similarity order.

duck 2.407698154449463

shark 2.6156086921691895

seal 2.919170379638672

dragon 3.653167486190796

ghost 3.685438394546509

buck 3.8235340118408203

green 4.058343887329102

brush 4.30176305770874

bow 4.380235195159912

robin 4.401726722717285

drill 4.477200508117676

spell 4.515389442443848

pool 4.539621353149414

spring 4.544600009918213

wake 4.570087432861328

pie 4.608753681182861

ham 4.763392925262451

tube 5.037248611450195

grace 5.125988960266113

trip 5.132474899291992

australia 5.255494594573975

cotton 5.462995529174805

dice 5.54638147354126

france 6.609094142913818

newyork 7.1939191818237305

Right off the bat, the centroid cat captures nicely animal cluster, surprisingly including even the imaginary one. However, the centroid for [newyork, australia, france] omitted newyork, plus centroid’s word is prohertrib, which seems not a valid word. It could be a derived token during the corpus preprocessing, before train GloVe.

This reminds me of another obstacle of our Turing test: the agents must be easily derived from the clue to produce a convincing win to the human evaluator. In other words, it’s good to come up with a clue, but better if it’s accompanied by a definable semantic link that connects the corresponding agents…

Another codebook, but breathe into life by humankind

Before the era of Deep Learning, most researchers put lots of hope in a rich human-labelled dataset. They expect that they can cultivate a good ML model that successfully captures intricate concepts defined by experts in the field at the end of the exhausting labour effort. Despite its root as a lexical database in psycholinguistics, on the same trend, WordNet cannot escape from the keen eyes of computer scientists, hence becomes known as a “concept tree”, re-interpret and use as AI knowledge-based application.

The literature of WordNet is vast. In the third proposal, I only care about the super-subordinate relation, also called hypernym/hyponym. To not disappoint my professors, I would carefully state this is an over-simplified understanding in exchange for the ease in readers’ mind.

WordNet contains concepts, structured in a hierarchy representation. Each concept, or syn(nonym)set, groups words that are interchangable in certain context together. A synset is a more specific category of its hypernym and a broader category than its hyponyms. If such a relationship exists between two synsets, there is a semantic link connects them.

An example of one possible synset for the word dog, when tracing bottom-up to its hypernyms:

dog, domestic dog, Canis familiaris

└──canine, canid

└──carnivore

└──placental, placental mammal, eutherian, eutherian mammal

└──mammal

└──vertebrate, craniate

└──chordate

└──animal, animate being, beast, brute, creature, fauna

- Wikipedia -

A synset is denoted by a tuple of word, its Part-Of-Speech, and its index. One can also retrieve its definition and lemmas, i.e. words can use to express the concept. For example:

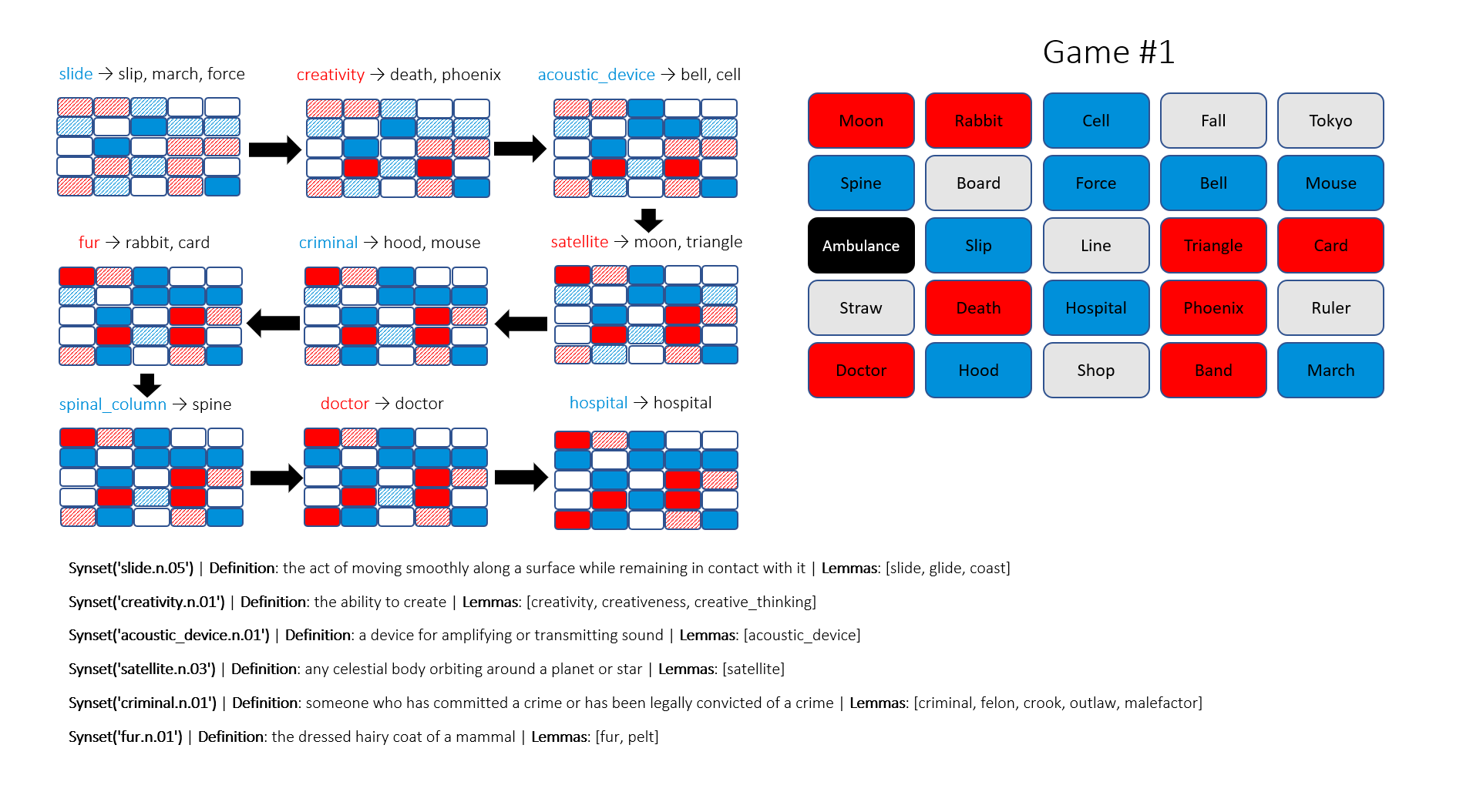

Synset('slide.n.05') | Definition: the act of moving smoothly along a surface while remaining in contact with it | Lemmas: [slide, glide, coast]

Synset('satellite.n.03') | Definition: any celestial body orbiting around a planet or star | Lemmas: [satellite]

Lastly, there exist functions to compute the similarity score between any synset pair. A sharp reader could have found the missing piece in our puzzle by now. Synset can play the same role as the centroid vector, while the definition gives us a mean to establish the clue-agents connection. Here is the proposed algorithm to generate a clue:

Input: blue agents, and the rest. Output: a list of tuple (word, count).

- We retrieve each blue agent’s hypernyms, storing into the set \(H_1\).

- We form all possible synset pairs from blue agents. From each, we retrieve their common hypernymns and store into the set \(H_2\).

- \(H_1\) union \(H_2\) to form \(H\).

- For each hypernym in \(H\), count how many blue agents in the proximity of the hypernym without being violated by any non-blue agents. Rank them in decreasing order of count and output.

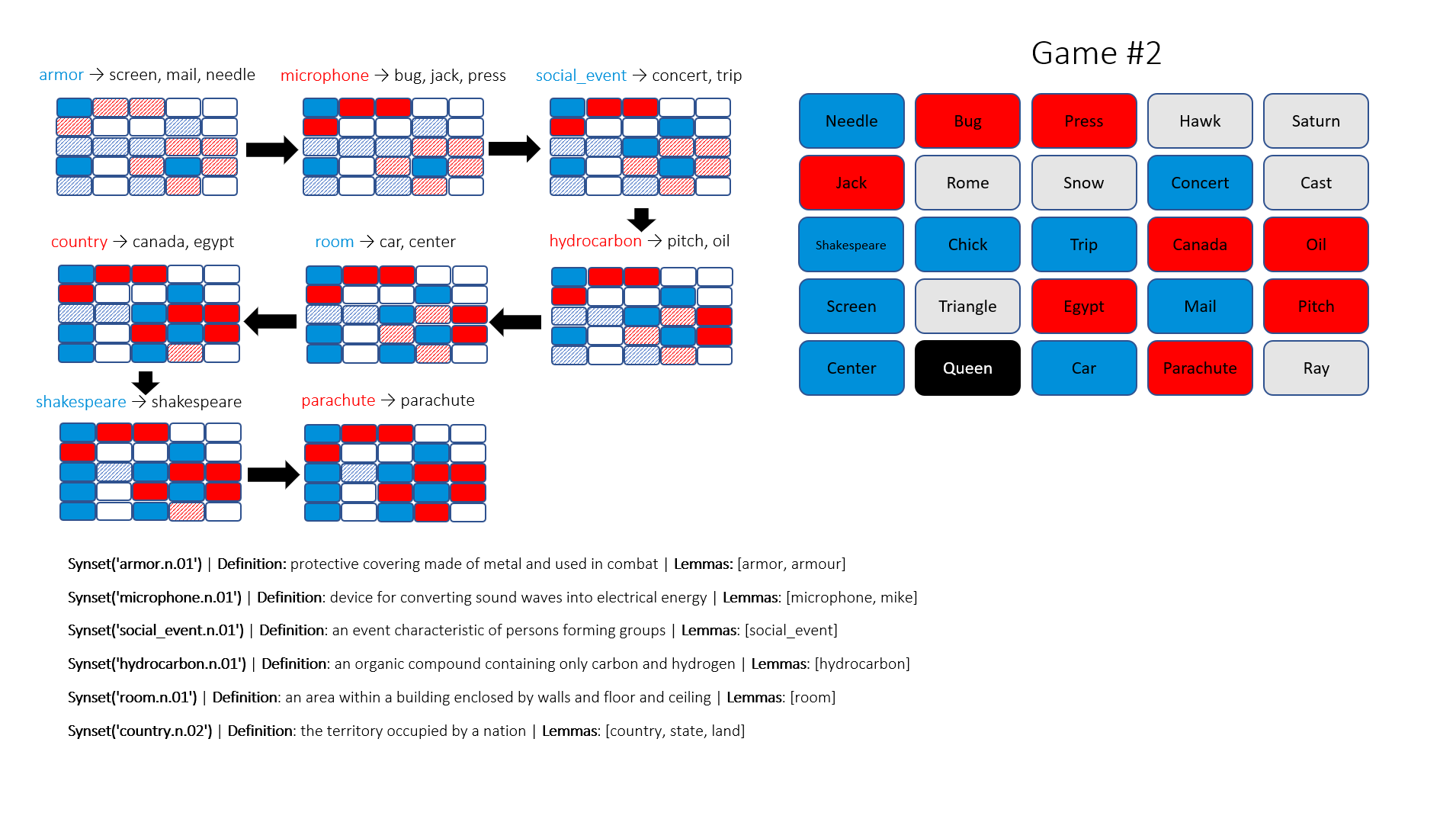

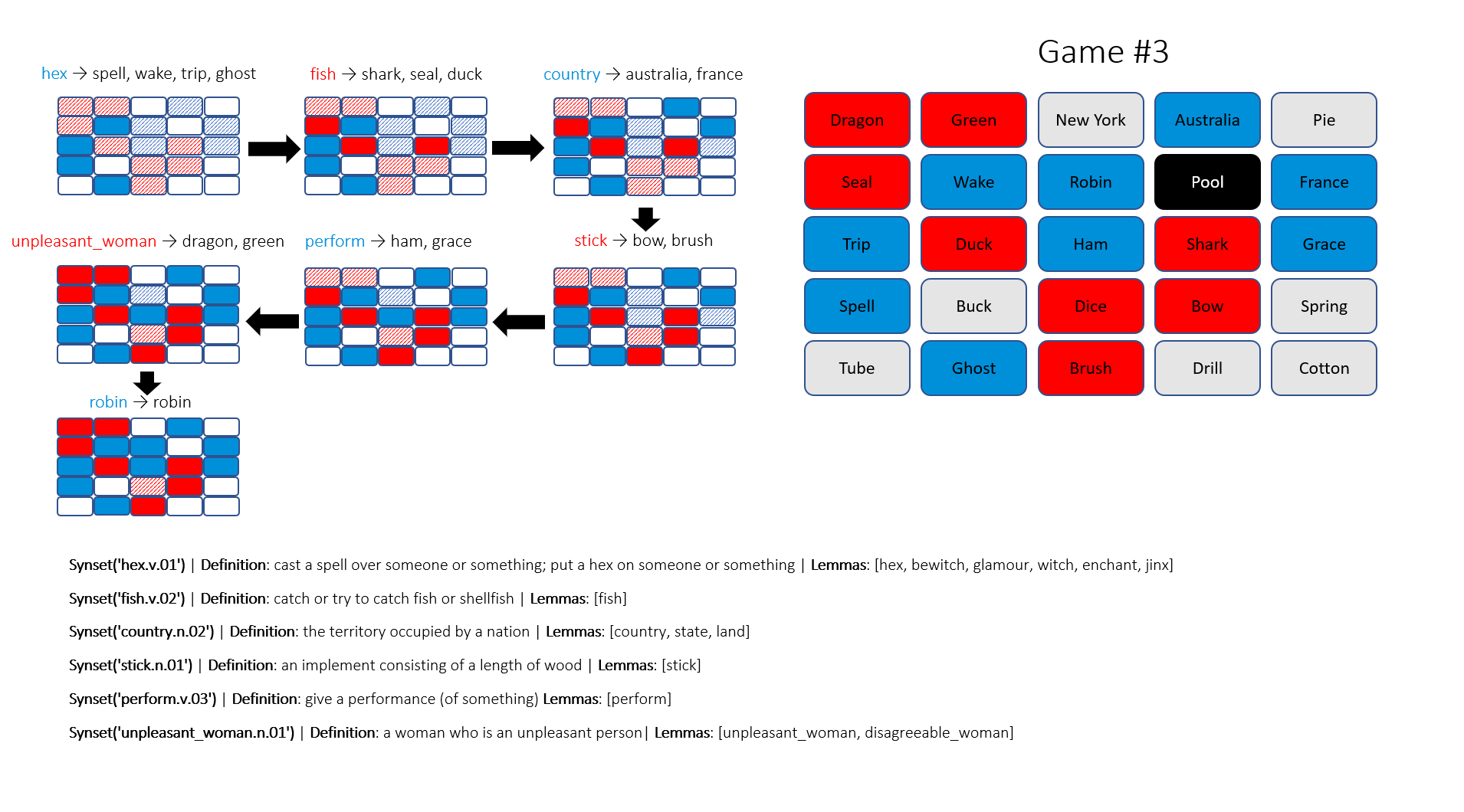

Sadly, the top results do not always make sense, so I use my judgement to pick the sensible one that covers as most agents as possible. This results in a suboptimal solution that does not guarantee a sure-win as intended and lasts for more than one turn. I have run three games with the proposed algorithm, the Blue team wins two out of three in seven and nine turns, respectively. My readers, I would be pleased if you can help be my evaluator, and share your thoughts if these moves are perceived as human or not!

There are fascinating insights that are helpful to players, for example, hydrocarbon and fish. And I wonder if criminal and hood are direct references to the legendary outlaw or not. However, those like unpleasant_woman, assume this is a valid word, a normal human-being unlikely to accept its link to dragon and green. At an attempt to defend my algorithm, I would say this is a Shrek reference.

This Github repo contains code to produce the above result. My thanks to Chuang Ning for the three games.