An OOP Approach to Implement A Sudoku Solver

in Blog

Code: Github

Introducing an Object‑Oriented Sudoku Solver in Python

I first encountered Sudoku Programming with C by Giulio Zambon last year, and it struck me as a surprising exploration of algorithmic solving techniques. The book walks through thirteen strategies: starting from the most basic eliminations and gradually building toward more intricate logical deductions. Zambon notes that he briefly considered an object‑oriented approach but ultimately chose a procedural style for accessibility.

Reading it, I couldn’t help thinking: I beg to differ. Many of the algorithms would have been cleaner, more expressive, and easier to extend with the right OOP abstractions. And if Python had been as popular then as it is today, it would have been an excellent language to showcase those ideas.

So I decided to turn that thought into a small side project: re‑implementing the solver using Python and object‑oriented design. Solving Sudoku efficiently is, of course, the baseline requirement. But my real focus is on structuring the codebase for clarity, maintainability, and extensibility - qualities that OOP can support beautifully when used well.

The solving strategies I adopt are largely inspired by the book, centered around the classic approach of eliminating candidates from each cell until the solution naturally emerges. Other formulations - such as binary integer programming or Donald Knuth’s exact cover framing - are undeniably powerful and could be integrated into this architecture. But they fall outside the scope of this project.

In the sections that follow, I’ll walk through how I translate the puzzle into a set of interacting objects, how the solver orchestrates its strategies, and how the entire system comes together into a working implementation.

What is Sudoku?

Sudoku is a logic‑based number‑placement puzzle built on a deceptively simple premise: fill a 9×9 grid so that every row, every column, and every 3×3 box contains the digits 1 through 9 exactly once. There’s no arithmetic involved - just pure deduction. The puzzle begins with a partially filled grid, and the solver’s task is to determine the remaining digits using logical constraints.

At its core, Sudoku rests on three fundamental rules:

- Row Uniqueness: Each row must contain the digits 1–9 with no repetition.

- Column Uniqueness: Each column must also contain the digits 1–9 exactly once.

- Box Uniqueness: The grid is divided into nine 3×3 regions, and each region must include all digits from 1–9 without duplicates.

These constraints interact in surprisingly rich ways. Even a single given number can dramatically restrict the possibilities of its row, column, and box. Naturally, Sudoku is a constraint satisfaction problem. That framing makes it a perfect playground for exploring different algorithmic techniques, from simple elimination to advanced search, and in this project, for experimenting with object‑oriented abstractions that keep those ideas clean and modular.

The Idea

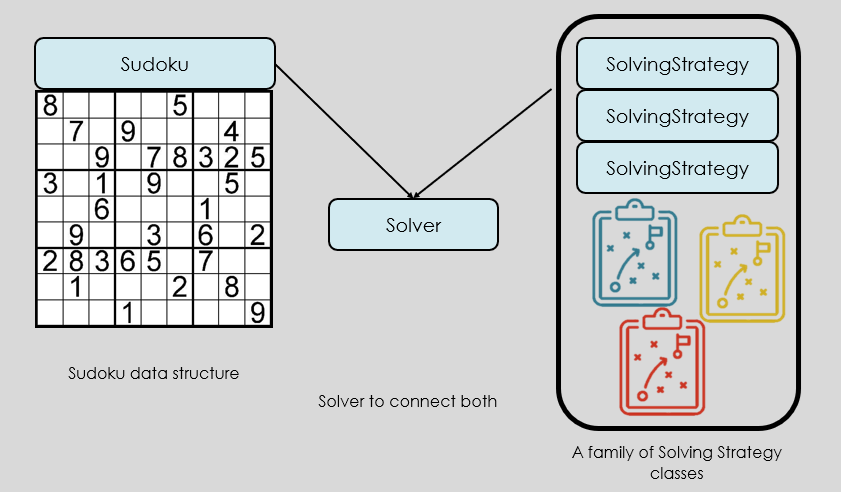

To keep the solver clean, extensible, and easy to reason about, the design revolves around three core entities: a Sudoku data structure, a family of SolvingStrategy classes, and a Solver that orchestrates everything. Each plays a distinct role, and together they form a modular system that mirrors how we tend to approach the puzzle.

Fig. 1. The concept of interacting entities.

Fig. 1. The concept of interacting entities.

At the heart of the system is the Sudoku grid itself. Instead of treating it as a plain 9×9 array, the design models it as a collection of objects that know about their own state and constraints. Each cell tracks its value and its set of candidates, while the grid provides convenient access to rows, columns, and boxes. This structure becomes the shared “source of truth” that every strategy operates on.

Each solving technique - whether it’s simple elimination, single‑candidate detection, or more advanced logic - lives inside its own SolvingStrategy class. These strategies all share a common interface, allowing the solver to apply them interchangeably. This separation keeps the logic focused and makes it easy to add, remove, or refine strategies without touching the rest of the system.

The Solver ties everything together. It holds a reference to the Sudoku grid and a list of strategies, applying them in sequence until no further progress can be made. The Solver doesn’t need to know the internal details of any strategy; it simply asks each one to “try to improve the grid” and checks whether any changes occurred. This orchestration pattern keeps the control flow simple while allowing the strategies to remain independent and reusable.

The Design

Sudoku Cell Management

At the foundation lies the SudokuCell: the smallest unit of the puzzle, yet one that carries all the essential logic for deduction. Each cell knows its position in the grid (row, column, and box), its current value (if solved), and its list of candidates - the digits it could legally take based on the puzzle’s constraints.

A cell is considered solved when its candidate list contains exactly one digit. Until then, it remains in a state of uncertainty, waiting for strategies to eliminate possibilities. This candidate‑driven design allows strategies to operate in a consistent and focused way: they don’t assign values directly but instead prune the candidate lists until only one remains.

To support efficient reasoning, each SudokuCell exposes:

- Row ID, Column ID, Box ID: These identifiers help locate the cell within the grid and its associated groups.

- Candidate List: A dynamic set of digits (1–9) that the cell could still legally take.

- Solved Status: A quick check—if the candidate list has length 1, the cell is solved.

While individual cells hold local state, much of Sudoku’s logic emerges from how cells interact within their groups: rows, columns, and boxes. Each of these is modeled as a SudokuCellGroup, a simple abstraction that wraps a fixed set of nine cells and provides a uniform interface for iteration and analysis.

class SudokuCellGroup(object):

"""An interface for a group of SudokuCell objects."""

def __init__(self, cells: List[SudokuCell]) -> None:

"""

Initializes SudokuCellGroup instance.

Parameters

----------

cells : List[Any]

A list of SudokuCell objects

"""

self._cells = cells

def __getitem__(self, index: int) -> SudokuCell:

return self._cells[index]

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self._cells)

class SudokuRow(SudokuCellGroup):

"""A class representing a row of cells in a Sudoku puzzle."""

...

class SudokuColumn(SudokuCellGroup):

"""A class representing a column of cells in a Sudoku puzzle."""

...

class SudokuBox(SudokuCellGroup):

"""A class representing a box of cells in a Sudoku puzzle."""

...

All groups—whether row, column, or box—implement the same interface, allowing external functions and strategies to loop through them intuitively:

for cell in cell_group:

# apply logic to each cell

Together, SudokuCell and SudokuCellGroup form the structural backbone of the SudokuPuzzle class. They encapsulate the puzzle’s state and expose just enough functionality to support modular strategies without leaking unnecessary complexity. You can write generic strategies that operate on any group type without worrying about internal structure.

class SudokuPuzzle(object):

"""A class representing a Sudoku puzzle."""

def __init__(self, sudoku_string: str) -> None:

"""

Initializes Sudoku instance.

Parameters

----------

sudoku_string : str

A string of length 81 containing the Sudoku puzzle to be solved.

The string should be a flat representation of the Sudoku grid,

with each character representing the value of the cell in the

order of row-major order.

Attributes

----------

grid : np.array

A 2D array of SudokuCell objects representing the cells in the Sudoku grid.

Valid indices are from (1,1) to (9,9).

rows : np.array

An array of SudokuRow objects representing the rows in the Sudoku grid.

Valid indices are from 1 to 9.

cols : np.array

An array of SudokuColumn objects representing the columns in the Sudoku grid.

Valid indices are from 1 to 9.

boxes : np.array

An array of SudokuBox objects representing the boxes in the Sudoku grid.

Valid indices are from 1 to 9.

Returns

-------

None

"""

self.grid = self.__setup_grid(sudoku_string)

self.rows = self.__setup_rows()

self.columns = self.__setup_columns()

self.boxes = self.__setup_boxes()

Solver and Strategies

Our design really shines once we reach the SolvingStrategy layer. Each strategy encapsulates a single logical technique, exposing a common apply() method that takes a SudokuPuzzle object, performs its deductions, and returns whether any progress was made. This uniform interface allows the SudokuSolver to treat all strategies the same way, regardless of complexity. Whether it’s a simple elimination or a more nuanced pattern, each strategy becomes a plug‑and‑play component.

class SolvingStrategy:

"""Base class for solving strategies."""

def apply(self, sudoku):

"""

Applies the solving strategy to the given Sudoku puzzle.

Parameters

----------

sudoku : SudokuPuzzle

The Sudoku puzzle to which the strategy is applied.

"""

raise NotImplementedError("This method should be overridden by subclasses.")

def __str__(self):

return self.__class__.__name__

class UniqueStrategy(SolvingStrategy):

"""Implements the Unique solving strategy."""

...

class HiddenCandidatePairStrategy(SolvingStrategy):

"""Implements the Hidden Candidate Pair solving strategy."""

...

While there are seven strategies that I have implemented in total, curious readers may check out the code for details. Here I only mention two representative strategies so you can get the general idea of their approaches.

The UniqueStrategy implements two of the most fundamental Sudoku deductions. It’s often the first strategy applied because it quickly clears out obvious constraints.

- Step 1: Propagate solved values. For every solved cell, remove its value from the candidate lists of all other cells in the same row, column, and box. This is the classic “basic elimination” step.

- Step 2: Identify unique candidates: Within each unit (row, column, or box), look for digits that appear in the candidate lists of exactly one cell. If a candidate is unique to a single cell in that unit, that cell must take that value.

The HiddenCandidatePairStrategy captures a slightly more advanced pattern: hidden pairs. This doesn’t immediately solve the cells, but it tightens the search space and often unlocks further deductions.

- Identify candidate pairs: In a unit (row, column, or box), find two digits that appear together in exactly two cells.

- Restrict those cells: If such a pair exists, those two cells must contain those two digits in some order. Therefore, remove all other candidates from those cells.

The SudokuSolver acts as the conductor. It receives a Sudoku grid and a list of strategies ordered from simplest to most complex. Its workflow is intentionally straightforward:

- Iterate through strategies sequentially: Apply each strategy in order.

- Restart when progress is made: If any strategy eliminates a candidate or solves a cell, restart from the first strategy. This ensures simpler techniques always get the first chance to act.

- Stop when solved or stuck: Continue looping until the puzzle is solved or no strategy can make further progress.

This feedback‑loop design keeps the solver predictable and efficient. It also makes the system easy to extend: adding a new strategy is as simple as implementing the interface and inserting it into the list.

class SudokuSolver:

"""Solves Sudoku puzzles using a sequence of solving strategies."""

def __init__(self, strategies: List[SolvingStrategy] = []) -> None:

self.strategies: List[SolvingStrategy] = strategies

def solve(self, puzzle: SudokuPuzzle) -> SudokuPuzzle:

"""

Solves the given Sudoku puzzle in place.

Parameters

----------

sudoku : SudokuPuzzle

The Sudoku puzzle to be solved.

"""

if len(self.strategies) == 0:

raise ValueError("No solving strategies provided.")

last_total_number_of_candidates = puzzle.count_total_candidates()

while True:

# Try each strategy in sequence

strategy_index = 0

current_total_number_of_candidates = last_total_number_of_candidates

while strategy_index < len(self.strategies):

strategy = self.strategies[strategy_index]

puzzle = strategy.apply(puzzle)

current_total_number_of_candidates = puzzle.count_total_candidates()

made_progress = (

current_total_number_of_candidates < last_total_number_of_candidates

)

if made_progress:

break

else:

strategy_index += 1 # Move to the next strategy

has_solved = puzzle.is_solved()

no_new_progress = (

current_total_number_of_candidates == last_total_number_of_candidates

)

if has_solved or no_new_progress:

break

last_total_number_of_candidates = current_total_number_of_candidates

return puzzle

Pieces Clued Together

With the building blocks in place - the puzzle structure, the cell groups, the strategies, and the solver - the entire system comes together in a surprisingly compact way. A complete run requires only a few lines of code:

from sudoku.sudoku import SudokuPuzzle

from sudoku.solver import SudokuSolver

from sudoku.solver import strategy as Strategy

puzzle = SudokuPuzzle(

sudoku_string="000000010400000000020000000000050407008000300001090000300400200050100000000806000"

)

solver = SudokuSolver(

strategies=[

Strategy.UniqueStrategy(),

Strategy.HiddenCandidatePairStrategy(),

]

)

puzzle = solver.solve(puzzle=puzzle)

Experiments on Minimum Sudoku

To understand how well the solver performs in practice, I ran a series of experiments using a well‑known dataset from Minimum Sudoku. This project investigates a classic open question: What is the smallest number of clues a Sudoku puzzle can have while still guaranteeing a unique solution?

So far, no 16‑clue puzzle with a unique solution has ever been found. However, there are many known 17‑clue puzzles, and researchers have collected as many as possible in hopes of uncovering deeper structural insights. My test set consists of 49,151 distinct 17‑clue puzzles, courtesy of Gordon Royle and The University of Western Australia.

Running my solver across the full dataset produced an encouraging result: 46,412 out of 49,151 puzzles were solved successfully, or 94.4% of the dataset. Given that these puzzles are intentionally minimal and often extremely constrained, this is a strong outcome for a purely logical, strategy‑based solver.

Which Strategies Matter Most?

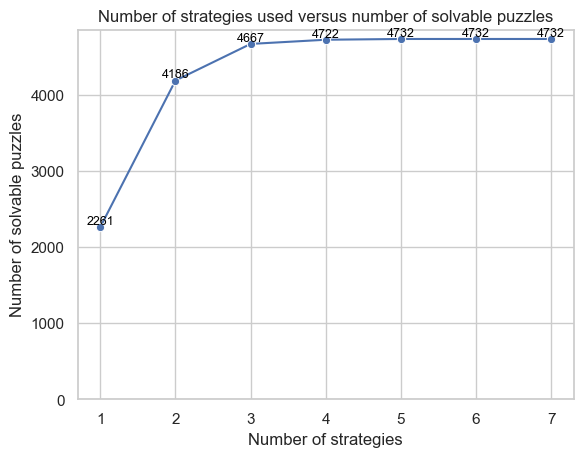

To explore the impact of strategy selection - especially under computational constraints - I evaluated all combinations of strategies on the first 5,000 puzzles. The goal was to identify the most effective subset when only a limited number of strategies can be used.

A few clear patterns emerged:

- UniqueStrategy is indispensable.

It is the minimum requirement for solving any puzzle in the dataset. Without it, no combination succeeds. - RectangleCornerReductionsStrategy is the next most impactful.

With only UniqueStrategy + RectangleCornerReductionsStrategy, the solver already handles over 80% of the puzzles. - Additional strategies offer diminishing returns.

Beyond the first two, each added technique contributes only marginal improvements.

Fig. 2. The experiments on the maximal puzzles can be solved using a limited number of strategies.

Fig. 2. The experiments on the maximal puzzles can be solved using a limited number of strategies.

These findings reinforce the value of a modular design: strategies can be mixed, matched, and evaluated independently, making it easy to tune the solver for performance, completeness, or computational efficiency.

Summary

Building a Sudoku solver through an object‑oriented lens turns what could be a tangle of ad‑hoc logic into a clean, modular system. By separating the puzzle state, the solving strategies, and the orchestration logic, each component stays focused on a single responsibility. SudokuCell and SudokuCellGroup provide a structured foundation, the SolvingStrategy classes encapsulate distinct deduction techniques, and the SudokuSolver ties everything together through an iterative, feedback‑driven loop.

What emerges is a solver that’s not only effective but also easy to extend, experiment with, and reason about. Even when tested against challenging 17‑clue puzzles, the architecture proved robust without resorting to brute force.

You can check out the complete code at my Github repo 👉 sudoku-solver.